Perceptual constancy is the ability to recognise the smell of freshly baked bread when walking past a bakery just as easily as standing right in front of the oven. This ability extends to our other senses too. We can identify a loaf of bread whether it’s 10 cm or 10 m away. Despite the vast differences in what our sensory cells receive—more olfactory receptor neurons firing up close and more photoreceptors contributing to the up-close loaf —our brain maintains a consistent perception. Perceptual constancy is crucial for making sense of the world. We aren’t born with this skill; as infants, we have to learn that objects have stable properties, even though our sensory input can vary with distance and environment. However, little is known about the neural changes that enable perceptual constancy.

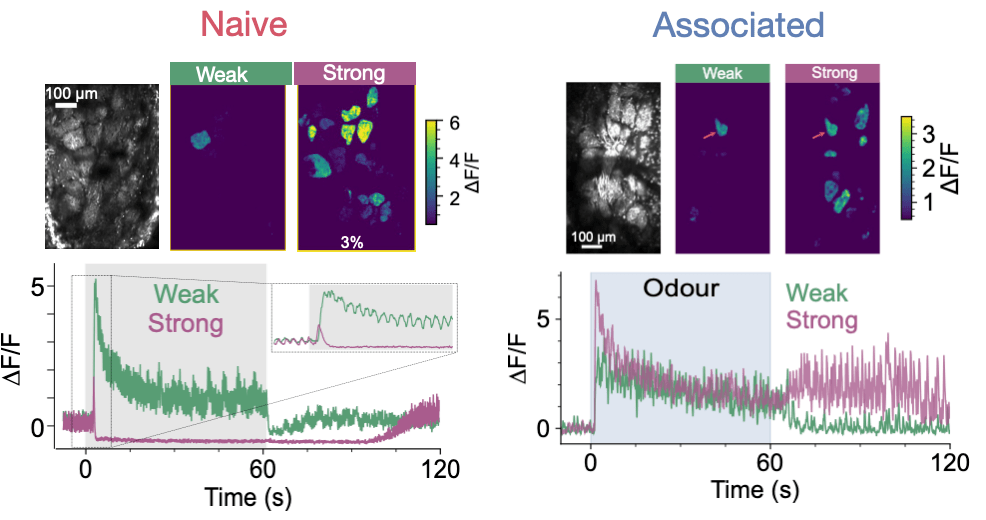

In this project we used behavioural experiments to show that when naïve to an odour mice lack perceptual constancy, perceiving high concentrations as distinct from weaker concentrations. Using 2-photon imaging of the activity of olfactory bulb circuitry we show that this perceptual shift coincides with transmission failure from olfactory receptor neurons that are most sensitive to the odour.

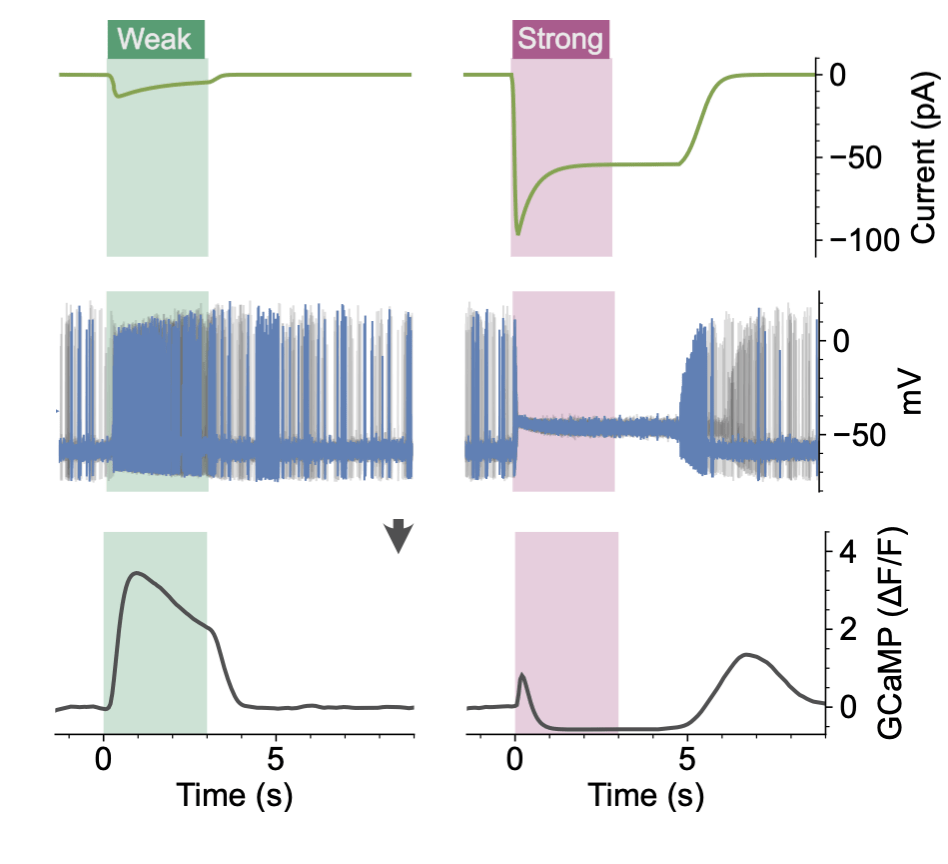

Using a computational model of the input to the olfactory bulb, we demonstrate that a sensitivity mismatch in olfactory receptor neurons results in transmission failure. At higher concentrations, the receptor current locks the receptor neuron in a depolarised state, preventing recovery of voltage-gated sodium channels, thus preventing signals from being transmitted along the olfactory nerve. The model is available on our github page

We then demonstrated that once mice have experienced the odor associated with food, they perceive a wide range of concentrations as food, even those that naïve mice perceive differently. This development of perceptual constancy is linked to a significant change in neural activity. Specifically, we observed a substantial shift in the sensitivity of the most sensitive olfactory receptor neurons, which prevented transmission failure.

This work shows, for the first time, that the plasticity of the primary sensory organ enables learning of perceptual constancy.